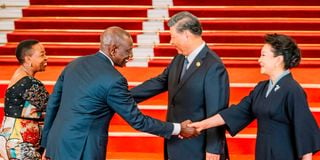

President William Ruto arrives in China on October 15 for the third Belt and Road Forum.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Prime

Ruto seeks multiple credit sources to deal with liquidity crisis

What you need to know:

- The Kenyan leader has taken up shuttle diplomacy in a bid to stabilise the economy wracked by a myriad of issues such as low production, high taxation and the wars in Ukraine and Palestine.

Kenya’s President William Ruto this week clocked his 38th foreign trip in his first year in office, in a whirlwind search for support for his administration’s Bottom-Up economic model to fulfil pre-election promises to an increasingly impatient electorate.

Dr Ruto was in Saudi Arabia to attend the Future Investment Initiative, which he used to market Kenya as an investment destination, and its readiness to sell carbon credits, a lucrative asset for developing countries.

This came a week after he returned from China for the 3rd Belt and Road Initiative in Beijing, where he sought money for growing the economy and jumpstarting some of the ongoing development projects.

This week in Riyadh, Dr Ruto did not hide the fact that he had joined supporters of the green transition, away from fossil fuels, even though the host, an oil-rich nation, is likely to continue producing oil for the next few decades. He sought more of its petrodollars for carbon credits.

In June, some 16 Saudi firms, including Aramco and Saudi Electricity Company, bought over 2.2 million tonnes of carbon credits from Kenya, paying more than $13 million. Dr Ruto sought more to provide liquidity for the economy hit by external and domestic shocks.

The Kenyan leader has personally taken up shuttle diplomacy to provide assurances to investors, in a bid to stem the free fall of the shilling, buffer forex reserves and stabilise the economy wracked by low production, high taxation, interest rates and commodity prices, besides the lingering effects of Covid-19 and the wars in Ukraine and Palestine.

A lower-than-expected annual growth has been forecast as a result of the obtaining liquidity crisis caused by declining revenues, high import bill, high debt repayment costs, and high fuel prices as the President intensifies debt-seeking missions abroad to stem the downturn.

A government source told The EastAfrican that one of the most urgent needs is to settle the $2 billion Eurobond maturing in June 2024 and funding infrastructure projects, particularly the extension of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Naivasha to Malaba.

The Northern Corridor SGR is a joint project with Uganda, and Kenya is under pressure to guarantee movement of the rail to the border for Kampala to start construction. The two partners are looking for at least $6 billion from multiple lenders towards the project, which stalled after China, the initial financier, pulled out.

President William Ruto and First Lady Rachel Ruto are received at the Great Hall of the People during a State banquet hosted by President Xi Jinping for visiting Heads of State and government in Beijing, China, on October 17, 2023.

Earlier, the two nations indicated that a way forward would be announced in November.

The Kenyan leader therefore finds himself under pressure to get the much-needed funds to kickstart the next phase of the project.

His tax reforms, which have seen him raid the pockets of salaried workers and small businesses to widen the revenue base, don’t seem to have worked. Indeed, the Kenya Revenue Authority this week told Parliament that it had fallen short of its first quarter target by Ksh79 billion ($525 million).

Financial barriers

President Ruto has spoken of the difficulty for African countries to get credit.

“If we want to go to the market, it's six percent more than the developed nations to access (money from the financial institutions, and that is if you are lucky, or it's seven or eight times more,” he told the panel discussion in Riyadh. “The global community should eliminate financial barriers and allow a fair market. It is very hard to get concessional funding…and that’s why we should reform the financial institution to not like Africa as credit risks.”

According to him, countries like Kenya deserve easier terms, given their human and natural resources, which should be included in calculating risk.

But he is finding it hard to plug a growing budget deficit, and now, in its first mini-budget, his administration has cut development expenditure by Ksh41.96 billion ($278.9 million) while increasing its maiden budget by Ksh187.3 billion ($1.24 billion). And a Ksh10 trillion ($66.7 billion) debt is hanging on the government’s head like the proverbial sword of Damocles.

Dr Ruto is seeking funds from China, the Gulf States and Europe, while negotiating with the multilateral lenders, World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for more funding and restructuring of old debt.

China, the usual go-to lender for Kenya’s infrastructure needs, has recently changed its financing strategy for Africa, viewing the continent as risky and coming up with stringent lending conditions.

This year, African countries are expected to pay $68.9 billion in external debt service, according to One Data &Analysis, a platform that focuses on economic, political and social changes impacting Africa.

At least 21 low-income countries on the continent are in, or at risk of debt distress while eight countries are already in debt distress.

China is Kenya’s third largest external creditor, accounting for 19.1 percent of the total external debt, after the World Bank’s International Development Association (29.1 percent) and the international sovereign bondholders (20.1 percent), according to data from the National Treasury.

Nairobi is looking for money to pay off its 10-year Eurobond valued at $2 billion and fund its SGR.

The SGR line from Mombasa to Naivasha was financed by the Chinese at a cost of $4.7 billion and the government intends to prioritise Phase 2B and 2C of the project. Phase 2B from Naivasha to Kisumu is estimated to cost $2.68 billion, while the last leg, 2C, from Kisumu to Malaba, will take another $896 million.

As at June 30, 2022, the amount of Kenya’s outstanding debt to Chinese Exim Bank was $849.53 million while that of the government of China was $10.2 million, according to Treasury figures.

Kenya’s repayment of its debut Eurobond issued in 2014 is seen as key to the restoration of international financiers’ confidence in the government’s ability to meet its financial obligations when they fall due.

Central Bank of Kenya Governor Dr Kamau Thugge recently said that negotiations are underway with the World Bank for a two-to-three-year reform programme under the development policy operation that is expected to unlock $750 million.

“Finally, we will be having the sixth review of the IMF in June next year and from it, we should get another disbursement of roughly $530 million. So over the next few months, we would be expecting to get quite a significant amount of concessional resources,” he said.

“We have continued to engage them (foreign investors) so we think that going forward the fact that we have removed that uncertainty about what we are going to do about the Eurobond is going to help mobilise foreign exchange coming into the economy.”

Government sources told The EastAfrican of the “constrained fiscal space in terms of available resources to fund anything else beyond what is already in the books.”

The National Treasury has also revised its growth forecast this year to 5.6 percent, from 6.1 percent, as per the approved 2023 Budget Policy Statement. Last year, the economy grew by 4.8 percent.

According to the IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis (2022) report, Kenya is already in breach of four of the six debt sustainability indicators, including the public debt-to-GDP ratio and the public debt-to-revenue and grants ratio. Others are external debt-to-exports ratio and the debt service-to-exports ratio.

“This essentially means that the country is at a significantly higher risk of debt distress,” a Kenya Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) bulletin says. “The breach of the external debt to exports ratio is especially worrying, because it implies that the country is not generating enough forex from exports to comfortably service its external debt.”

Revenue collections have fallen below target, against rapidly growing expenditure requirements, with debt servicing costs taking up close to 50 percent of the monthly revenue collections.

The National Treasury says Ksh475.59 billion ($3.17 billion) worth of external debt is maturing this financial year, and Ksh281.45 billion ($1.87 billion) in the 2024/2025 fiscal year.

Additionally, Ksh289.46 billion ($1.92 billion) and Ksh 311.34 billion ($2.07 billion) external debts are maturing in the 2025/2026 and 2026/2027 fiscal years respectively.

“We are expecting large inflows from our multilateral development partners. For example, we have the IMF, which is coming here next week, and we expect by December, based on the ongoing programme, to get at least $400 million,” DrThugge told a Parliamentary Committee on Finance and Planning. “We have engaged with them and told them we need extra funds, and that will be part of the discussions. How much we will get, we don’t know, but that is an issue on the table for further discussion.”

Yet, the IMF and World Bank may not cater to Kenya’s urgent development needs. Officials say without Chinese funding the big-ticket projects may not move.

With Beijing playing hardball, is Saudi Arabia the Plan B?

If it is, economists warn that it may not be a better lender. If Kenya were to get funding through the Saudi Fund for Development, which usually targets projects or budget support in developing countries, the interest would be high.

Saudia backs countries that are debt-ridden or poor, through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT), which is IMF’s main vehicle for providing concessional financing to low-income countries. PRGT loans are interest-free, but target programmes that help stimulate additional financing from donors, development institutions and the private sector. Saudi Arabia pledged to lend $3.76 billion through PRGT this year.

Nairobi and Riyadh have a recent history of debt that has not seemed to go as President Ruto sold it to Kenyans. In March, Nairobi signed an oil supply deal with three Gulf-based companies, which was designed to manage demand for dollars.

Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi National Oil Co and Emirates National Oil co-signed the deal allowing Kenya to switch from an open tender system in which local companies bid to import oil every month. The government said this would make fuel cheaper but, today, petrol retails at an unprecedented Ksh217.36 ($1.44), one of the highest rates on the continent. The shilling this week breached the 150 mark in exchange for the dollar, with fears of further weakening. The oil deal has since been extended to December 2024, with the government saying this is meant to “drive down the freight and the premium costs”.

The deal comes with 180-day credit terms, allowing Nairobi to build up dollars for the purchase over time, rather than requiring $500 million every month to pay for imports. Currency traders, however, say this is tantamount to postponing demand. The rise in the cost of fuel and other fiscal measures that have impacted the economy have been pushed by the IMF.