Bongo Flava erodes moral values? Not the whole truth

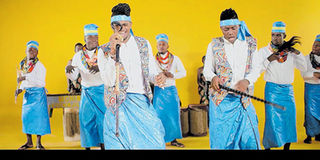

Diamond Platnumz with his WCB dancers during the making of his sampled version of hit ‘Salome’ video , a song that was originally done by Saida Karoli.

PHOTO I FILE

What you need to know:

- I present my critique by first referencing his arguments---and the assumptions that rest upon them--- but I also offer alternative views.

In last Sunday’s The Citizen, Justice Rutenge abominates our beloved Bongo Flava for “eroding basic moral values.” Mr Rutenge’s arguments are comprehensive and thoughtful, however, I disagree with his claims.

I present my critique by first referencing his arguments---and the assumptions that rest upon them--- but I also offer alternative views.

First, Mr Rutenge motivates his arguments by using Kenyans’ disgust of Tanzanians on social media through Kenya’s Twitterati’s #KickTanzaniaOutOfIG that emerged early this year as evidence of our moral decadence.

This assumes that Kenyan elites on social media represent a majority of Kenyan public opinion of Tanzanians, which it may, but from the popularity of both our artists and our President in Kenya, seems unlikely that those views by a few Kenyan elites represent a consensus opinions of Tanzanians among Kenyans.

Mentioning Kenyan elite views also assumes that we, Tanzanians, should necessarily listen to these Kenyan elite voices, which we may not want to do. Kenyan elites continue to wish that we “return” Mount Kilimanjaro to them, for instance, while others have moved whole archeological sites north of our border, as Raila Odinga’s daughter, Rosemary Odinga “erroneously” did in her remarks at a youth forum at the United Nations headquarters in the United States’ New York City in 2015.

Second, Mr Rutenge argues that although some of these explicit sexual content in music and in society existed for decades before the present day---except in the late 1990s during his adolescence, it seems--- he is mostly alarmed with the emergence of this content into the mainstream and the acceleration of such a trend. I am unsure whether this is necessarily true because music like the late Bi Kidude’s Muhogo wa Jang’ombe is certainly sexually explicit and cannot be deemed outside of the mainstream. Neither are the many various Taarab songs such as Khadija Kopa’s Mwanamke Mambo or the various Congolese ndombolo dance musical genre or the Kilimanjaro Band’s Kachiri outside of the mainstream. So the question Mr Rutenge asks whether “…the current sex references [are] a mere reflection of changing social values or are they pushing the boundaries of what has been historically regarded as socially acceptable and unacceptable?” is an apt question indeed. I learn more on the latter than the former, if at all.

Moreover, Mr Rutenge seems to be ambivalent about whether to view the changing of our culture as a good or bad phenomenon. At some instances he laments the deterioration of our society’s morals through racy tabloids, whose actions he puts “at the epicentre of the fast progressing ecosystem of moral rottenness [emphasis mine]” while at other instances he seems to appreciate the lack of elitism in our music when he calls Singeli an emergent “least elitist genre of music” which “is loved.” His surprise about how non-elite music can be popular is misplaced. One of the great things about Bongo Flava is its ability to appeal to vast swaths of society in Tanzania and far beyond our borders as our music rings from a small battery-powered radio on the slopes of the Virunga volcanic mountains in the Democratic Republic of Congo or to the DJ’s deck on the sandy shores of Moroni in the Comoros.

Fourth, Mr Rutenge’s view that it is ironic that “Diamond Platnumz and his WCB label…enjoy a big reputation in society…” because their songs have explicit sexual content assumes that their reputation is only a function of the content of some of their songs. Mr Platnumz is defined not just by Salome but by Mbagala and many other releases, with Number 1 being among his magnum opus. Bongo Flava artists’ reputations are more so a function of their ability to entertain millions of people, which in turn translates in significant economic and geo-political value for Tanzania as they bear our flag from Lagos to Los Angeles.

Fifth, Mr Rutenge’s laments on “a class of female socialites [who] are gaining significance at a rather alarming rate” is male-centric at best and sexist at worst. Does Mr Rutenge feel threatened by women “gaining significance” or is it that they are gaining it “at a rather alarming rate [emphasis mine]”? To be fair, he does later clarify when he goes on to say “because of their sex symbolism.” I am unsure whether he realizes that what his fears reflective is a larger general problem in our society and that is how men treat women.

Are these new female socialites who use sex on social media to shepherd herds of their followers on Instagram, for instance, doing so only because of those platforms or are the platforms an expression of the choices left to these women? Regardless of the answer, women’s bodies do not require the state to regulate them---men do that sufficiently enough. From getting cat-called to getting groped to getting one’s clothing ripped off in public for dressing “inappropriately” women’s bodies are, if anything, over-regulated already.

Additionally, such regulation of what women can and cannot wear is part of a larger problem of blaming women for men’s sexual behaviours. Mr Rutenge laments that “our views on promiscuity” are deteriorating moral values yet he does not lament about how a promiscuous woman is always seen as “wicked” while a promiscuous man is celebrated for his masculine “prowess”.

Mr Rutenge seems frightened that women such as Gigy Money, whose appearance on the show Take One led to TCRA banning it, are garnering a lot of fame through their hundreds of thousands and at times millions of followers on Instagram, for instance. This fame, however, isn’t just for its own sake because Gigy Money--- as well as many other women, who are not just “selling sex” but advertising their businesses that may range from fabric and makeup to event planning--- are wielding growing economic power in ways unseen before in our patriarchal society. This is a good thing. The Economist magazine reports on October 17th of this year that social media celebrities can garner up to $5,000 or Sh10.9 million for advertising business products on Instagram, a reward for having anywhere between 100-500,000 followers on that platform. Women making money is a great thing and social media is breaking traditional barriers for countless of women in Tanzania and around the world.

Penultimately, calling on the “Regulator” to oversee individuals, as Mr Rutenge would have us do, will most certainly adversely impact not just people such as Gigy Money, admittedly a controversial figure, but also disproportionately thousands upon thousands of women who are doing business that I am sure Mr Rutenge himself wouldn’t object to in mainstream ll over the country and abroad.

Social media is liberating these women from traditionally restrictive environments to be more captains of their fate and masters of their own destinies. This is a good thing and should be applauded and encouraged. Women almost always feel the “pinch of regulation”, as Mr Rutenge calls it, disproportionately more so than men. Regulating social media is equivalent to regulating women.

Ultimately, I would like to end on two important notes. The first is to thank Mr Rutenge for penning his piece because one of the healthiest things in a democracy is discourse, even when it is contrarian to one’s own views and it is important that as young Tanzanians we cultivate and sustain our abilities to amicably agree to disagree. The second is to end by reminding the reader, Mr Rutenge in particular, that culture isn’t a static entity. It changes. All of the time. Our own culture has evolved from not seeing nudity as sexual to seeing it as sexual; from seeing breasts as asexual to now increasingly seeing them as sexual objects, affecting many mothers from comfortably breast-feeding their children in public.

Cultural change isn’t always positive, at least not in line with our idiosyncratic normative beliefs, but it is negotiable. Our divergent views on Bongo Flava and social media are a testament to this negotiation. I am optimistic that the equilibrium our culture is heading toward is in the right direction and I am, unlike Mr Rutenge, less certain that our morals are in fact deteriorating. Religiosity, for instance, seems to be on the rise, judging from all the new churches and mosques whose membership rises unabated annually. I urge the reader, and Mr Rutenge, to be hopeful and, through dialogue and nonviolent action, to continue perfecting the morals of our society.

Gladness Saule works with Alistair Company Limited and the views presented here do not necessarily reflect those of Alistair Company Limited. Ms Saule can be reached via e-mail on [email protected] and you can follow her on Twitter @gladysaule and on Instragram @gladysaule.