Prime

How France veto threat ended Dr Salim's UN Secretary General ambitions in 1996

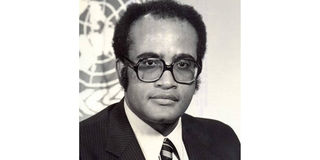

Dr Salim Ahmed Salim

What you need to know:

Dr Salim's name was, eventually, never submitted as UN Secretary General candidate despite South Africa's strong intention to do so amidst the threat by France to veto any non-French speaking candidates

Dar es Salaam. Towards the tail end of 1996, the race to replace UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali began, despite the fact that he had received the support of 14 of the 15 members of the United Nations Security Council for his second term.

The United States found sufficient reason to veto his re-selection, ultimately compelling him to withdraw his candidacy.

Consequently, this action led to the opening of the seat for other potential candidates.

It was the second time a UN Secretary General had served a single term.

It was still Africa’s turn, and only an African candidate could stand for the position.

The open selection went into deadlock as France vetoed all candidates from English-speaking countries.

On the other hand, the US vetoed all candidates from French-speaking countries and even offered to throw its weight in favour of Tanzania’s Salim Ahmed Salim, whom they had vetoed after winning the 1981 selection by one vote.

Newly released excerpts from Dr Salim's diary published in his archives show that many African capitals were in support of Salim’s candidature.

But the newly released documents give a glimpse of the events that unravelled in Dr Salim’s attempt to vie for the UN Secretary General seat.

On top of the negative forces that he had to deal with was France's readiness to veto his candidature.

In their view, for Dr Salim to become United Nations Secretary General, he had to speak French. They did not mince words.

French President Jacque Chirac, through his advisor on African affairs, Monsieur Dupuch, on a December 5 dinner with Dr Salim’s Director of Cabinet, Said Djinnit, made it clear that they were determined to use command of the French language as a prerequisite.

"I am sorry for Salim. We like him, but the language factor for us is very important,” he told Djinnit.

Given France’s position, Dr Salim advised that it would not be wise for them to present his candidature as they monitor developments in Paris.

“I told Joe Legwaila that, given the position of France, it would be unwise to present my candidature. Joe and I agreed that we should continue to monitor the situation while efforts are being made to persuade France to show flexibility,” he writes in his diary.

But as Dr Salim and his team weighed out the possible options that were available, the following day, South Africa made a move with an announcement in New Delhi, backing Dr Salim's candidature.

“I was watching CNN around 1700 hours local time when I heard that Vice President Thabo Mbeki had declared in New Delhi full support for my possible candidature as UNSG,” he writes.

According to Dr Salim, the announcement had caught him unaware, and at that juncture, he thought it was unwise given the earlier developments.

“It also came amidst a number of developments earlier today, which all led to the conclusion that it was neither wise nor desirable for my name to be presented given what was becoming the increasingly clear French opposition for linguistic reasons—irrational as that may be given France's support for my candidature in 1981,” he notes.

At this point, it had become clear that France was not a willing party, a position that he briefed President William Mkapa after his consultations with President Blaise Compaore and General Sani Abacha after the Ouagadougou Summit.

“Rather, consultations should be intensified with a view to determining the bottom-line position of France and, in the process, attempting to persuade them to demonstrate flexibility,” he writes.

There were further consultations that involved the then Tanzania’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete, and another diplomat only referred to as Ambassador Kibello.

At that meeting, though there were other pressing issues such as the sanctions against Burundi and the Eastern Zaire (now DRC) question, it was agreed that it was important to establish how far the French were prepared to compromise on the language issue.

“If their position of insistence becomes a conditional prerequisite, then clearly my candidature is still-born, and thus there is no point in having my name presented,” he writes.

But even when he was certain that France’s position would not change regarding the language issue, a new development emerged: South Africa was not giving up the idea.

In a telephone conversation with the Deputy Director General for Multilateral Affairs and Organisation in the Department of Foreign Affairs, Abdul Minty, from Pretoria, Dr Salim was informed of South Africa’s position and was ready to submit his candidature immediately.

“I was told that after consultations between President Mandela and Deputy President Thabo Mbeki and others, President Mandela has decided not only for South Africa to support me but to formally present my candidature to the President of the UN Security Council,” Dr Salim writes.

Though they were conscious of France’s position on the issue of language, South Africa did not believe that it was enough to make France veto his candidature.

According to Minty, President Nelson Mandela had separately engaged Presidents Bill Clinton and Jacque Chirac and was set to brief him.

South Africa held the view that France’s vetoing of Salim’s candidature would be a declaration of confrontation, and their interests in Africa would be affected in many ways.

“I maintained that a confrontation would not help anyone, and certainly not me. Furthermore, such a confrontation, besides the fact that it will not lead to my election, has the potential to create division within our own ranks,” reads the diary notes.

He pointed out that, as Secretary General of the OAU, he had achieved some success in bridging the differences between the Anglophone and Francophone blocks in Africa in the seven years he served.

“I cannot, therefore, afford to do anything that could be used to rekindle the Francophone-Anglophone divide and, in the process, undermine all that I have been fighting for,” he concludes.

Dr Salim’s name was never submitted, and France eventually changed its veto to an abstention, and Kofi Annan of Ghana was selected Secretary-General for a term beginning January 1, 1997.