Prime

How Tanzania's T-Bond boom is reshaping private sector lending

What you need to know:

- Analysts are warning that the shift may be straining the supply of credit to businesses and households

Dar es Salaam. Tanzania’s booming Treasury Bond market is drawing historic levels of investor interest, offering government a reliable source of domestic financing.

However, the surge is creating ripple effects in the financial sector, especially in the availability and cost of credit to the private sector.

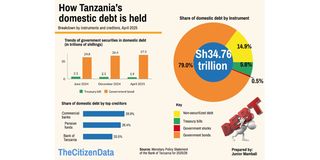

By the end of April 2025, the country’s domestic debt stock had reached Sh34.75 trillion, marking an 8.8 percent increase from June 2024. Treasury bonds alone contributed Sh2.7 trillion to this rise, with their share of total domestic debt soaring to nearly 80 percent from Sh24.75 trillion in June 2024 to Sh27.45 trillion ten months later.

While the figures highlight the growing dominance of bonds in government financing, analysts are warning that the shift may be straining the supply of credit to businesses and households.

Record-breaking appetite for bonds

In April 2025, the government’s 20-year bond auction received Sh760 billion in bids, and in May, a 25-year bond shattered previous records with Sh794 billion in subscriptions—the highest ever for any bond auction in Tanzania.

This strong appetite is driven largely by institutional investors such as banks and pension funds. Zan Securities Advisory and Research manager Isaac Lubeja described the bond market as being at a historic high, but cautioned that this enthusiasm has come with trade-offs.

“As more funds are locked into long-term bonds, banks are left with less liquidity for business loans, mortgages, and other credit products,” he said.

According to the Bank of Tanzania (BoT), commercial banks now hold 28.9 percent of all government bonds, making them the single largest category of bondholders. Pension funds follow at 26.4 percent, while the BoT itself accounts for 20.5 percent.

Private credit under pressure

Private sector credit grew by 15.1 percent between July 2024 and April 2025—an increase, but a slowdown compared to the 18.4 percent seen during the same period a year earlier. The BoT attributes this moderation to a deliberately tight monetary policy aimed at containing inflationary pressures driven by shilling depreciation.

Thus, while bond yields climb and attract institutional capital, businesses find it harder to access affordable credit.

Despite ongoing reforms, lending rates remain high—averaging 15.5 percent, barely changed from last year. The BoT, in its June 2025 Monetary Policy Statement, acknowledged that lending rates have remained “downward sticky,” reflecting limited pass-through of monetary policy to borrowing costs.

To address this, the government and central bank have implemented a series of measures, including, monitoring banks’ adherence to financial consumer protection regulations, expanding national ID coverage and formalising residential addresses to improve credit profiling and strengthening the judicial system to fast-track loan default disputes. It is also finalising a price comparison system to improve borrower decision-making and conducting lgal reforms to ease collateral recovery and expand the definition of acceptable security to include movable assets.

These efforts aim to reduce structural impediments to lending and deepen financial inclusion.

Investment banker and corporate advisor Salum Awadh noted that rising bond yields are logically influencing bank lending behaviour.

“It’s rational for banks to prefer higher-yield, low-risk bonds over lending to riskier borrowers,” he said.

However, Mr Awadh also emphasised that bond yields are just one of many factors affecting lending rates—others include cost of funds, inflation, overheads, and borrower risk profiles.

The shift is evident in interbank markets. Mr Lubeja noted that both the overnight and 7-day interbank lending rates have consistently hovered near the BoT’s 8 percent ceiling since the beginning of the year—an indicator of tightening liquidity.

“These elevated rates spill over into the wider credit market, raising the cost of borrowing across the board,” he said.

BoT acknowledged the strain and has attempted to inject liquidity through various tools, including reverse repos, foreign exchange purchases, swaps with banks, and gold purchases.

The role of CBR and benchmark effects

To enhance monetary policy signalling, BoT introduced the Central Bank Rate (CBR), set at 6 percent throughout the 2024/25 fiscal year. The CBR is meant to guide interbank rates and eventually influence lending rates.

Mr Awadh welcomed the move, noting its alignment with practices in developed markets, but warned that significant impact will require time and policy consistency.

Meanwhile, seasoned banker Kelvin Mkwawa cautioned that long-term government bond yields, especially 10-year bonds currently yielding around 14.25 percent, are acting as informal benchmarks for loan pricing.

“If the benchmark is 14.25 percent, banks will understandably add a margin for risk and overhead, which keeps lending rates elevated,” he said.

He called for measures to reduce the government’s borrowing appetite and make private sector lending more attractive to banks.

Academic view: Crowding out not yet total

A senior finance lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam Business School, Dr Tobias Swai, said that while government borrowing competes with the private sector, it does not necessarily crowd it out completely.

“Legal and prudential regulations, including liquidity ratios, limit the extent to which government borrowing can absorb credit at the expense of private lending,” he explained.

Still, the long-term trend is clear. Tanzania’s bond market is booming—but that success is reshaping the country’s lending landscape. The challenge now is striking a balance between supporting public investment and sustaining private sector growth.