Prime

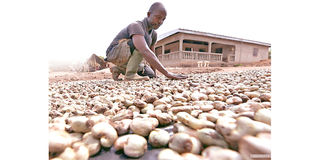

Raw deal: How unprocessed cashews deny Tanzania billions

What you need to know:

- Tanzania, expected to produce over half a million tonnes in 2025, stands as one of Africa’s giants in this trade. While 87.5 percent of its nuts sail raw to India and Vietnam (only to be resold to Europe at more 4.5 times the value), if the status quo remains, this raw-export addiction will cost Tanzania $1.73 billion cumulatively by 2030, enough to lift 800,000 farmers from poverty.

In 2024, the world produced an estimated 5 million tonnes of raw cashew nuts. Remarkably, 60 percent of the raw nuts feeding the global appetite came from African soil and were swiftly shipped to factories in Asia. From Benin and Côte d’Ivoire to Tanzania and Mozambique, the raw nuts depart for foreign grinders and brands, forcing African nations to forfeit billions of dollars each year.

Tanzania, expected to produce over half a million tonnes in 2025, stands as one of Africa’s giants in this trade. While 87.5 percent of its nuts sail raw to India and Vietnam (only to be resold to Europe at more 4.5 times the value), if the status quo remains, this raw-export addiction will cost Tanzania $1.73 billion cumulatively by 2030, enough to lift 800,000 farmers from poverty.

The cashew’s journey to Tanzania is a tale of colonial extraction echoing into modern economics. Portuguese traders carried the resilient tree from Brazil’s tropics in the 16th century, planting it along East Africa’s coastline. Yet centuries later, the pattern persists: raw resources flow out, value flows elsewhere.

Today, on a single acre with 50 mature cashew trees, a grower can harvest 5-10 kg of raw nuts per tree each season. With farmgate prices of about $1,200/tonne, a maximum season calendar yields $600 annually. Yet this income arrives only after three years waiting for a first crop—and it takes six to nine years to hit peak yields, leaving farmers exposed to volatile raw-nut prices and the whims of international buyers long before they see a stable return.

But globally, cashews are a $12 billion luxury market, growing at 5.3 percent annually. Raw nuts sell for $1,200/tonne, but cleaned, shelled kernels fetch $6,560/tonne. Roasted? $12,000. Branded retail packs? $25,000+. Tanzania’s 2025 production could generate $200 million more if processed. The potential isn’t just revenue; it’s transformation.

For Tanzania to harness that potential, though, there are four mountains to climb: capital, competition, entry barriers, and policy.

1. Capital chasms: According to Dr Eric Mkwizu, financial analyst at UDSM’s Business School, building a 4,000-tonne/year processing plant costs $1.5 million. Technology is readily available—from European high-end lines to more affordable units from India or China—but the larger hurdle is working capital: Buying 4,000 tonnes of raw nuts at Sh2,000/kg demands $3.1 million upfront—per plant. When auction prices spike to Sh3,500/kg, this balloons to $5.4 million.

2. Costly competitors: Tanzania’s energy costs are 2–3× higher than Vietnam’s; labour productivity lags 30 percent behind India’s. Shelling 1 tonne of RCN costs $150 in Tanzania versus $90 in India and $70 in Vietnam. Without scale, local processors will struggle to match the Asian giants.

3. Market fortresses: Indian conglomerates like Olam and Vietnam’s PAN Group control 65 percent of global kernel trade. Their distribution monopolies freeze out new entrants. Add to that the complexity of accessing established global supply chains, where Indian and Vietnamese firms dominate. The status quo feeds a trade industrial complex that extracts margins without empowering local actors.

4. The policy vacuum: Export bans flip-flop. Tax incentives vanish mid-season. Power fails sometimes for days. Investors can handle risk, but what they cannot handle is the policy environment which is as unpredictable as monsoon rain on a tin roof – deafening, destabilising, and impossible to plan around.

Unlike Tanzania, Vietnam offers a masterclass in value capture: Vietnam’s cashew kernel exports soared from just 286 tonnes valued at $1.4 million in 1990 to 730,000 tonnes worth $4.37 billion in 2024. This was achieved through three decisive moves. One, government loans covered 40 percent of German shelling machines to slash labour costs. Two, cluster farming connected 200,000 smallholders to factories through co-ops, ensuring a stable supply. Three, year-round operations by sourcing raw cashew nuts from around the world during Vietnam’s off-season to maximise plant uptime. The result? Vietnam now commands 40 percent of global cashew processing capacity.

Tanzania doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. A multifaceted approach could unlock homegrown value: First, the government must champion enabling policies—tax incentives for local processors, guarantee affordable and priority power access, and streamline customs procedures for spare parts. Second, leapfrog legacy tech: launch modular $500,000 grading plants, thus capturing 20 percent value addition overnight and deploy AI sorting machines from India/China at 30 percent of European costs. Third, establish robust farmer-processor linkages—through cooperatives or outgrower schemes—to ensure a reliable supply of quality nuts at fair prices, securing both livelihoods and raw material volumes. Fourth, implement a phased rollout that builds local expertise before progressing to roasting, flavouring, and branded packaging.

Let me say that Tanzania needs more than an incremental change but a value-capture insurgency. At the current rate, the value that Tanzania is forfeiting is so high – we are too comfortable living with the neo-colonial economic structures. But the trees that Portuguese ships once dropped off now stand as a test: Will Tanzania choose sovereignty? The machinery humming in Bình Phuoc and Gujarat’s factories, hiring tens of thousands of employees—paid for by Tanzanian nuts—holds our answers.

The rule of the game in the cashew business is ‘process or perish’.

Charles Makakala is a Technology and Management Consultant based in Dar es Salaam