What Kibaki did 20 years ago

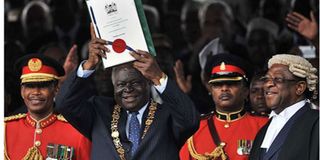

On August 27, 2010, former President Mwai Kibaki lifts Kenya's constitution after it was promulgated at Uhuru Park in Nairobi. PHOTO | AFP

This week, exactly 20 years ago, newly elected Kenya President Mwai Kibaki named a 22 cabinet list. Kibaki had led one of Africa’s largest democratic opposition coalitions, the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), to victory over the Kenya African National Union (Kanu).

NARC’s triumph ended nearly 40 years of one-party rule and was the first electoral victory by the opposition in the old East African Community (comprising Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda).

Kibaki’s next ten years were to be dogged by corruption scandals and the disastrous late-2007-early-2008 post-election violence following his disputed re-election. However, through it all, he still pulled off the most spectacular economic and social turnaround ever seen in an African country following a regime change that happened peacefully, without an armed rebellion or an uprising. By 2012, Kenya was being celebrated as the great African Silicon Savannah and touted as the most technologically innovative country in Africa and among the elite in the world. Safaricom’s mobile money service M-Pesa was all the rage, and it was being touted as the next world changer. At the Mobile World Congress, the largest mobile event in the world, people hang on to the words of Safaricom’s honchos.

There is now a firm view that Kibaki made possible most of the best things about Kenya today or laid the foundation for them. The man even gave the seemingly perpetually cash-strapped Kenyan government budget surpluses. Admittedly, the Kibaki-glorification has a rosy and revisionist element, but there is no denying that he let the magic out of the bottle.

One of the difficult things is explaining why Kibaki achieved that success with relative ease compared to the period that followed his tenure. I was in the back of a room at a recent event where, after some grim pictures were painted about the state of several African economies and the debt crises they faced, the question turned to what lessons could be learnt from the Kibaki era. He succeeded in an otherwise turbulent world, including the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.

His first cabinet was full of meaty opposition leaders and others who had fallen late with the Kanu government led by President Daniel arap Moi. The coalition, not surprisingly, became very fractionalised, and the in-fighting was extraordinary. The divisions in government were seen as a failure. Now, perhaps with perfect hindsight, someone argued that the fights were one of the reasons Kibaki succeeded. He said probably at no time in Kenya’s history has policy contention been so sharp. The result, he argued, is that in the heated dispute, only the very best ideas survived. Kenya, apparently, doesn’t work very well when there is harmony in government.

Another view was that Kibaki had a few old-school, arrogant ministers who didn’t particularly care if people screamed at their actions. The best example was John Michuki, who was appointed Minister for Transport and Communications in January 2003.

Michuki took the most ungovernable and stubborn entity in Kenya, the matatu industry, and brought it to order, refusing even to lift his head when they shut down the country. He floored them. People like Michuki are rare in African politics today.

Also on the table was the idea that Kibaki sprinkled his government with stars. Mukhisa Kituyi, who was appointed as Minister for Trade and Industry, became a celebrity figure in Africa’s battle to get its perspectives in World Trade Organisation (WTO) negotiations. He went on to become the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) seventh Secretary-General. “Kenya hasn’t had figures like Mukhisa who are a sure shoo-in for big international positions since the Kibaki era”, he said. There was a murmur or two in the room but no noticeable disagreement.

The point was made that when it came to Permanent Secretaries (today Principal Secretaries) and, especially, Under-secretaries, Kibaki “didn’t play politics, and was blind to tribe”, appointing some of the best and brightest. People like human rights and good-governance campaigner John Githongo, appointed anti-corruption czar, fell out very quickly and put it all in a searing book, “It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower”. Seems the Kibaki men and women didn’t eat everything.

Bitange Ndemo, an open government data and digital evangelist, was appointed Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Information and Communications. People like him fought to ensure that Google Maps took off work on the ground in Kenya first and was a champion of M-Pesa.

Fellows like Githongo, and there was a couple of them in the Kibaki government, have never been allowed on the political high table again. Ndemo was put out to pasture and only appointed ambassador in the dying months of President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government last year.

Kibaki himself was a fiscal conservative and mean with money. He was an old man and no longer paying school fees for children. He came to power at the right time too, when the “African Decade” was taking off. Put all that in a pot, and you have the “Kibaki magic”. Hard for all those elements to come together again for another leader.