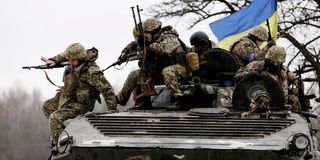

Ukrainian soldiers take part in a training exercise some 10 kilometers away from the border with Russia and Belarus in the northern Ukrainian region of Chernihiv on February 2, 2025. PHOTO | COURTESY

On February 27, 2025, we dissected the three justifications Russia has offered for its invasion of Ukraine: halting Nato’s eastward march, denazification, and demilitarisation. We concluded that while these arguments contain fragments of legitimate concerns, they fall woefully short of justifying a full-scale invasion. This leaves us with a lingering, crucial question: What does Russia truly want in Ukraine?

Just a day after the publication of the above-mentioned article, a high-profile meeting between Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky and Donald Trump at the White House ended in diplomatic disaster. Instead of signing the proposed deal, Trump, flanked by VP JD Vance, sharply criticised Zelensky. Trump was incensed that Zelensky insisted on securing a security guarantee from the Americans, rather than signing the deal that would have granted the Americans more than $500 billion in rights to Ukrainian mineral resources.

The incident was revealing. For Zelensky, the pursuit of security guarantees isn’t just about military aid—it is about insulating Ukraine from further aggression. His demands underscore a fundamental fear: if Ukraine remains vulnerable, it will once again fall prey to the spectre of Russian control.

This brings us to a central point in understanding what Russia wants in Ukraine. The public justifications Russia has offered mask a deeper objective: that Ukraine should remain a weak, subjugated, and subservient state, unable to challenge Russian hegemony. By preventing Ukraine from joining Nato, Russia effectively denies it a robust defensive framework. By branding Ukraine as a bastion of Nazism, Russia seeks to suppress its nationalist resistance and delegitimise its government. And by calling for demilitarisation, Russia aims to cripple Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against further incursions. Ukraine is Putin’s war of choice: it is not about ensuring security per se, it is about ensuring that Ukraine never stands as a state that can control its destiny.

The repercussions of Russia’s strategy in today’s world are far-reaching. That’s why I am shocked by the response I see in Africa. While, for instance, public opinion polls initially indicated support for Ukraine, Africans have remained quite tepid and neutral in providing practical support. Many of our intellectuals clearly sympathise with Russian narratives—we even blame Ukraine for being invaded. They had it coming, we say. So, why do they insist on a security guarantee, even at the risk of losing everything?

Zelensky’s demands are not born of ambition or greed; they are rooted in a genuine fear of Russian aggression. Understanding his urgent pursuit of security guarantees is critical here. Ukraine has every reason to be wary: past security assurances, notably the 1994 Budapest Memorandum—in which Ukraine surrendered its nuclear arsenal in exchange for protection from Russia, the U.S., and the U.K.—proved fatally inadequate. In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and fomented separatist movements in Donetsk and Luhansk, shattering any semblance of territorial stability. Now, Ukraine seeks binding security commitments that can deter further Russian incursions. It is looking for a model akin to the U.S.-Israel relationship—a strategic alliance that provides both military aid and an enduring guarantee of political and economic stability.

Yet, we must ask why Russia’s neighbours are desperate to flee Moscow’s orbit. Yes, Nato is expanding east, possibly unwisely so, but the story is much more nuanced: Russia’s neighbours are running westwards. Nato’s doubling in size since the Cold War, now encompassing 32 nations, including former Soviet states, ex-Warsaw Pact members, and Russia’s neighbours, underscores this exodus. Despite its immense size, military might, and long history, Russia continues to lose partners. Is there something wrong with Russia?

A few weeks ago, I asked one retired Tanzanian general: If given the choice between joining a Western alliance or remaining in Russia’s orbit, how many of Russia’s neighbours would choose Moscow? The answer is chillingly illustrated by Moscow’s actions: since 1991, Russia has invaded four ex-Soviet states: Lithuania, Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia. If Russia can only maintain allegiance through the omnipresent threat of violence, then its appeal as a partner is fundamentally hollow. One can see why the Ukrainians are resisting Russia.

The differences in the value propositions between the two sides are stark: one side offers democratic and progressive values, and the other offers autocratic and regressive tendencies. Thus, Ukraine’s struggle is not merely about resisting an external aggressor—it is about asserting the right to a future defined by progress rather than one imposed by force and historical revisionism.

Putin is a master strategist. Ukraine was a major strategic gamble for him, and if he succeeds, he will reshape Eurasia’s geopolitics forever. Sadly, that means the world will regress into a geopolitical era determined by coercion and subjugation.

Again, what is wrong with Russia? Putin and his envoys abroad speak so casually about Ukraine not returning to its 2014 borders. Why is it that wherever Russia goes, nations lose territories? Finland, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Poland, Baltic nations – I mean everywhere?

In the coming articles, we will continue to probe the strategic currents that drive Russia’s actions. Only by understanding the full scope of Russia’s ambitions can we hope to craft an effective response to one of the most consequential geopolitical challenges of our time.