Prime

Ajit Hoogan Singh: The unsung architect who shaped Zanzibar skyline

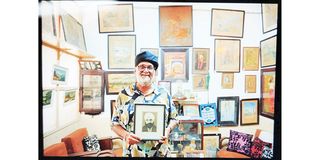

Parmuk Singh, proudly displays a collection of his uncelebrated grandfather, Ajit Singh’s paintings and architectural drawings, artefacts that shed light on the visionary behind much of Zanzibar’s urban transformation. PHOTO | CORRESPONDENT

What you need to know:

- According to documents, Ajit Hoogan Singh's only recognition came in 1947 when he was awarded the Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar by the then Sultan Seyyid Khalifa bin Haroub upon recommendation by the British Government

Unguja. Ajit Hoogan Singh remains one of the island’s architects who left a lasting impact on Zanzibar’s architectural landscape, yet little is rarely said about him.

With a portfolio blending African, Indian, and European architectural influences, Singh’s work is a testament to his diverse cultural heritage and visionary approach to architecture.

According to documents, his only recognition came in 1947 when he was awarded the Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar by the then Sultan Seyyid Khalifa bin Haroub upon recommendation by the British Government.

Born in Punjab, India, Singh arrived on the shores of Zanzibar in 1936 at the age of 27, bringing with him extensive architectural knowledge and a passion for creating buildings that bridged multiple cultures.

Upon settling in Zanzibar, he joined the Department of Public Works as a draftsman and quickly became integral to the design and construction of many of the city’s most iconic buildings.

Despite his significant influence, Singh’s legacy has remained largely uncelebrated—an oversight that his family is working tirelessly to change.

The Citizen recently paid a courtesy call to the family home in Kikwajuni, Zanzibar, where a wealth of architectural treasures from Ajit’s portfolio are displayed.

The house itself, designed by Ajit Singh, is a striking blend of traditional Swahili architecture with European and Indian influences—a reflection of the architect’s multicultural background.

Built in stages over several years, the house stands as a microcosm of Singh’s architectural philosophy.

As his grandson Parmuk Singh describes it, the home features a European exterior, an Asian interior, and an African back—a combination that captures the diverse cultural elements Singh experienced throughout his life.

A window into the architect’s vision

Singh’s Kikwajuni residence, constructed in 1939, provides a glimpse into his evolving architectural style.

The house incorporates classic Swahili design elements, including Barazas (stone benches) at the entrance and a central courtyard with living spaces arranged to create a gradient of privacy.

Over time, Singh added modern two- and three-story structures to expand the living space, incorporating influences from both Indian and European architecture.

These additions were designed to provide greater comfort, yet they maintained the aesthetic balance between traditional and modern styles that defined Singh’s approach.

Singh’s contributions to Zanzibar extend far beyond his own residence. His work is scattered across the island, yet many of these buildings remain under-appreciated.

Singh was behind the design of several key public buildings, including the Civic Centre, the Old People’s Home in Sebleni, and the Natural Science Museum.

He also designed a range of residential and commercial properties, such as the Lemki Building and Auto Sales in Malindi, along with numerous houses for civil servants, including his own home.

In addition to his urban contributions, Singh played a vital role in shaping Zanzibar’s education and healthcare infrastructure.

Notable projects include the Haile Selassie Secondary School, Darajani/Vikokotoni School, Beit-el-Ras Teachers’ Training College, and the Main Hospital in Zanzibar Town.

His work also included significant contributions to public infrastructure, such as the Old Airport, Kizimkazi Lighthouse, and several police stations across Zanzibar.

One of Singh’s most ambitious, yet lesser-known projects, was his design for a luxury hotel at the historic Portuguese Fort at Forodhani Seafront in 1939.

This project, which aimed to transform the fort into an upscale destination, was halted by the outbreak of World War II.

While the hotel never materialised, Singh’s design for the fort’s gatehouse, completed in 1948, remains a standout example of conservation architecture.

The building, which was later converted into the Ladies Club, beautifully blends modern design with the fort’s historical elements.

A legacy in jeopardy

Despite Ajit Singh’s monumental impact on Zanzibar’s architectural identity, his work has gone largely unrecognised.

For Parmukh Singh, this lack of acknowledgment is not only a personal loss but a missed opportunity for the people of Zanzibar to appreciate the breadth of Singh’s influence on the town’s development.

Inside the family home, Parmukh proudly displays a collection of Ajit Singh’s paintings and architectural drawings—artefacts that offer a deeper understanding of the visionary mind behind Zanzibar’s urban transformation.

“Ajit Singh played a pivotal role in shaping Zanzibar’s architectural landscape, but his work is often overlooked,” he says.

“Through this collection and the awareness we’re raising, we hope more people will come to recognize the importance of his contributions—not only to Zanzibar but to the world of architecture as a whole.”

The challenges of preservationAjit Singh’s architectural projects were part of a broader effort to modernize Zanzibar’s infrastructure, spearheaded by the colonial administration, which sought to improve sanitation, water supply, and overall living conditions.

Many of the projects planned in the 1930s, including a major redevelopment of the Ng’ambo area, never came to fruition due to a lack of funding.

However, Singh’s vision played a crucial role in laying the groundwork for later developments in Zanzibar, including the post-revolutionary Michenzani flats.