Prime

How Kaiza rose from a goat herder in Bukoba to top cancer researcher in US

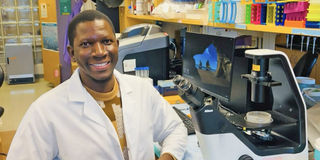

Medard Kaiza, a Bukoba man, who weathered the storm to become a leading researcher in the US. PHOTO | Courtesy

What you need to know:

- Medard’s journey began humbly, herding goats in his village. Yet, his innate curiosity and thirst for knowledge propelled him to excel academically

Medard Kaiza’s story reads like a Hollywood movie script; his chances of making it to the top of the science field, standing shoulder to shoulder with renowned scientists in Japanese and American universities, feel like a fairytale.

Dr Kaiza grew up herding goats in rural Bukoba, a village boy lifestyle that he still cherishes to this day, sitting behind his laboratory work at the University of Pittsburgh, where he is a cancer research scientist at their human cancer centre. ‘My work centres on lung cancer and head and neck; my goal is to find a cure for cancer and also make all the efforts to make sure cancer patients live a better and prolonged life,’ he explained.

Dr Kaiza’s research is based on immunology, focusing on understanding the cancer cells in the tumours that grow in patients and helping develop anti-tumour immunity. His work is very hands-on; he gets to extract the tumour tissues from patients and talk to them and see how they are doing.

His fulfilment comes from seeing that the patients’ lives get better. His insanely busy career and research projects have never stopped him from going back home to Tanzania; he is close to his roots, and that keeps him grounded and shapes his priorities. In November of 2024, he was back home, and young people looked at him in amazement at what he had been able to accomplish.

“They always ask me how a Tanzanian like myself is working at the prestigious University of Pittsburgh; they presume I am from a rich family or my father is a prominent person in Tanzania. I am not; I come from a very small village in Bukoba,” he said.

Dr Kaiza’s parents died of malaria when he was at a young age. Their death would push him into malaria research later in his study life, hoping that no Tanzanian child would have gone through the pain he went through losing his parents to a curable disease like malaria.

He went to Kibaha Secondary School, a government school, and later joined the University of Dar es Salaam for his undergraduate degree.

His trajectory in life changed when, against his friends’ advice, he took a scholarship opportunity that took him to Japan, where he took his PhD at Nagasaki University’s Institute of Tropical Medicine, Malaria Unit. Now the young man whose parents met their demise at the hands of this disease that has claimed an insurmountable number of African lives was on the global stage, where he would learn, research, and play a role to wipe out malaria out of Africa. He spent five years in Japan.

He has had several publications that go in depth about his work on malaria, one being “Beyond cuts and scrapes: plasmin in malaria and other vector-borne diseases,” which was published in 2021.

After half a decade in Japan, he was offered a position in the United States at the National Institute of Health (NIH), located in Bethesda, Maryland, just outside of Washington, DC, which allowed him to continue doing his research in Washington, DC.

“My PhD was in non-infectious diseases, specifically malaria, so I went to Maryland and continued my research with some very good scientists there,” he recalls.

His stint at NIH was a successful one, with research he was involved in being published and having media coverage about their findings.

Their research was on malaria and how malaria parasites were invading human immune responses. Basically, when someone gets infected, the malaria parasite has an asylum they implore to invade the immune system, and that’s why people get infected, he added.

He later switched to cancer research, which had always fascinated him, and that’s when he joined the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Centre. His work involves studying cancerous tissues.

After a patient has been through a doctor’s treatment, they extract body tissue, and with the permission of the patient’s loved one, the tissue lands at his table for further research in hopes of making a breakthrough and finding a better way to fight these agonising diseases.

“We can take the tumour and study the cells and see the condition of the patient, and that will determine what the doctor will prescribe for the patient,” he said. In the modern age, cancer cure research has been an elusive one, but consistency and focus are the keys that keep doctors like Kaiza optimistic about the days ahead.

“In research, 99 percent of the time it does work, but we focus on the one percent that don’t, and we work on that,” he mentioned. They did the findings and published them. He was the one leading the team of researchers. Now NIH is developing a malaria vaccine based on their findings.

The boy from Bukoba village would always return home; he is still in awe of how far he has come. His village, to this day, still struggles with poor roads and water scarcity, something he hopes he can do something about shortly.

“To whom much is given, much is expected, and I feel I have a responsibility to contribute intellectually to my people. I am still a member of my community,” he said. The community he comes from shows how humble his beginning was and how focus and determination can build one to success.

Dr Kaiza doesn’t think he is a genius or gifted, but he was just able to grab opportunities presented to him. When he was at the University of Dar es Salaam applying for a scholarship in Japan, he talked to his friends and urged them to apply too. They were all jobless, and his friends turned down the opportunity because it required them to learn Japanese for 6 months.

To Dr Kaiza, he was learning a new language for free as an added advantage. Life was not served on a silver platter; growing up an orphan, he knew that every chance he got was a blessing, and he knew that the only way out of poverty was education. He didn’t grow up in a family that could afford to give him millions for business capital.

“People say education is a great equaliser, and I agree with that,” he chimed. At NIH in Washington, DC, Dr Kaiza had already started a knowledge transfer initiative between NIH and institutions in Tanzania.

Recently the world has been bombarded with a lot of misinformation about science and mostly vaccines after the Covid-19 pandemic, fuelled by online posts that question science. Dr Kaiza said that if you want to know how vaccines work, you have to look at the early 1800s.

Life expectancy was 40 years old, but today it is in the 90s, and what changed was the development of different vaccines like polio and chickenpox, and that helped people live a better life and protect them against these diseases, and that is thanks to science.

Speaking of the current state of cancer in Tanzania, he hopes that as a country we can emulate what developed countries have done in terms of serving patients and the infrastructure built for cancer treatment and healthcare and do that in Tanzania. Can do the same He said services in developed countries do.

Medard hopes his story will spark the fire of love for science and bigger dreams among young Tanzanians. I am sure he looks at the long road he has taken and what he has contributed in the field of science, mostly in cancer and malaria that took his parents, and surely his parents would be proud of their son.