Prime

Tanzania at the Olympics: 50 years of missed opportunities

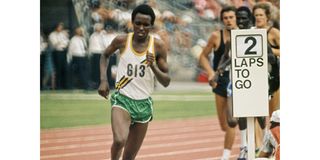

Filbert Bayi en route to the world record in the 1500m at the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand. PHOTO | GETTY IMAGES

What you need to know:

- Critics argue that Tanzania’s Olympic woes stem not only from poor performance but from a systemic failure rooted in inadequate preparation, lack of investment, and an over-reliance on football at the expense of other sports.

Dar es Salaam. As the Paris 2024 Olympics concluded yesterday in Paris, France, Tanzania’s participation once again underscored a harsh reality: 50 years of competing on the global stage, yet the nation’s Olympic dream remains largely unfulfilled.

With a record boasting no gold medals and only two silvers, one unavoidable question arises, why has Tanzania failed to capitalize on the Olympic Games, and what needs to change to alter this narrative?

Since its Olympic debut in 1964, Tanzania has consistently sent a small contingent of athletes to the multisport event, often overshadowed by neighboring countries like Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia, which return home with medals and national pride.

This year in Paris, Tanzania’s delegation consisted of just seven athletes. The lack of medals and the small size of the Olympic delegation point to deeper issues within the country’s sports development strategy.

Critics argue that Tanzania’s Olympic woes stem not only from poor performance but from a systemic failure rooted in inadequate preparation, lack of investment, and an over-reliance on football at the expense of other sports.

One issue drawing significant criticism is Tanzania’s dependence on the "universality card" to secure spots for its athletes. The universality rule allows countries with limited success in qualifying for the Olympics to send athletes to ensure diverse participation. This year, Tanzania sent two swimmers, Collins Saliboko and Sophia Latiff, and one judoka, Andrew Mlugu, under this provision. Unfortunately, their performances were far from stellar. Andrew Mlugu, who won his round of 32 judo match against Willina Tai Tin of Samoa, was defeated 10-0 by Frenchman Joan Benjamin Gaba in the round of 16 on July 29. This marked the beginning of Tanzania’s disappointments in Paris.

On July 30, 2024, swimmer Collins Saliboko failed to advance in the 100-metre freestyle, and on August 3, Sophia Latiff also failed to progress in her event. According to Filbert Bayi, Secretary General of the Tanzania Olympic Committee (TOC) and a former Olympic silver medalist, the reliance on universality entries is a symptom of a larger issue.

“These spots are for those who haven’t made the cut, and unfortunately, we’ve relied on them for years with no success,” Bayi said in an earlier interview. Bayi has been vocal about the need for athletes to qualify through competitive means rather than relying on the universality card, which he argues sets them up for failure.

The universality entries often include athletes who lack the rigorous training and competition experience necessary to compete at the Olympic level. This has led to consistently poor performances, as seen in Paris, raising questions about whether Tanzania is genuinely preparing its athletes for success on the global stage.

What are Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia doing right?

While Tanzania continues to struggle, neighboring countries like Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia have become powerhouses in athletics. Their success is no accident. These nations have invested heavily in sports infrastructure, talent identification, and early development programs.

“In Kenya, athletics is more than a sport—it’s a way of life,” said sports expert Thomas Odero. “From a young age, children are encouraged to run, with schools and communities providing the support needed to nurture future champions.”

Uganda has followed a similar path, strategically partnering with Kenya to allow its athletes to train alongside Kenyan champions. This cross-border collaboration has raised the standard of Ugandan athletes, enabling them to challenge Kenya on the track.

“The success of these countries is a testament to what can be achieved with proper planning and investment,” said South African-based sports analyst Andrew Kibet.

“Tanzania, on the other hand, has failed to see the Olympics as more than just a sporting event. It’s a source of national pride, a unifying force, and an economic driver—something Tanzania has yet to fully grasp.”

Kibet points to Botswana as an example. In 2024, sprinter Letsile Tebogo won Botswana’s first-ever Olympic gold medal in the 200 metres, prompting the country’s president to declare a national holiday.

“This recognition shows the importance of investing in Olympic sports,” Kibet said. “With Tanzania’s youthful population, there’s an opportunity to make the Games a central part of the nation’s identity.”

The benefits of winning an Olympic medal extend beyond national pride. Countries with successful Olympic programs often see increased tourism, sponsorship deals, and enhanced global visibility. For a nation like Tanzania, with its rich cultural heritage and natural beauty, Olympic success could be a powerful marketing tool.

“Tanzania needs to view the Olympics as an opportunity to attract foreign investments through sponsorships and gain a larger share of the Olympic preparations,” Kibet added. “The economic benefits are immense, but they require a commitment to investing in a broad range of sports.”

Incentives and Rewards

One area where Tanzania lags significantly behind its neighbors is in motivating athletes through incentives. In Kenya, athletes receive substantial allowances and bonuses for their performances.

Gold medalists earn Ksh3 million, silver medalists Ksh2 million, and bronze winners Ksh750, 000, in addition to rewards from World Athletics.

Uganda has also introduced cash prizes for its athletes, with gold medalists at the Paris Games promised USh100 million, silver medalists USh50 million, and bronze medalists USh30 million.

In the past, the two countries have even donated land, houses, and vehicles to their medalists.

In contrast, Tanzanian athletes often compete with little financial support or recognition. This lack of incentive not only discourages young people from pursuing sports but also limits the country’s talent pool. The Tanzanian government has acknowledged the need for change, particularly in its approach to preparing athletes for the Olympics.

The Ministry of Culture, Arts, and Sports has repeatedly promised to build a dedicated training centre in the Manyara region, a high-altitude area ideal for athletics. However, these promises have yet to materialize. Since 2016, the government has claimed it will construct this centre, but eight years later, the promise remains unfulfilled.

The centre was first proposed by then-Sports Minister Nape Nnauye in response to a question in Parliament in May 2016. The plan was to build the centre in Mbulu District to honour athletes like Filbert Bayi, who have brought pride to the nation.

Filbert Bayi (left) presents his singlet to World Athletics president Sebastian Coe during a ceremony held in Paris, France. PHOTO | AGENCIES

In an interview with The Citizen, Permanent Secretary Garson Msigwa acknowledged the delays, stating that the government is still in the process of finding a contractor. “We are looking for a contractor to begin construction of this modern centre that will host various athletics sports,” he said.

However, Msigwa did not specify the costs or a timeline for the construction.

Adding to the skepticism is the fact that the ministry’s budget for the 2024/2025 financial year includes no allocation for the Manyara centre. This omission, despite extensive plans for the renovation and construction of other sports infrastructure, raises further doubts about the government’s commitment.

A Paradigm Shift

Experts agree that Tanzania needs a comprehensive sports development strategy that goes beyond building infrastructure. This strategy should include talent identification, training, and support from the grassroots level.

“There needs to be a paradigm shift in how sports are perceived and prioritized,” said sports enthusiast Amina Mohamed.

“Schools should play a central role in this transformation by incorporating a diverse range of sports into their curricula. This approach would help identify and nurture young talent, instilling a culture of excellence and competitiveness from an early age.”

Mohamed also suggests that Tanzania look to its neighbors for inspiration. Establishing partnerships with countries like Kenya and Uganda could provide Tanzanian athletes with the exposure and competition they need to excel.

The government should also explore ways to incentivize sports participation through scholarships, sponsorships, and career opportunities for athletes. The journey to Olympic glory should not be borne by the athletes alone; it is a collective responsibility.